Yes I can. At least that’s what I told my mate at work 🙂

I’ve got a soft spot for EKO acoustic guitars. I bought one 1981 (my second guitar) and loved it. Made in Italy, with what I now know is an unusual bolt-on neck, it was solid and made from beautiful wood. The quilting on the back was so rich and pretty I can still remember how regularly I would just spin the guitar around to just look at it. It felt heavier and more robust than all my friends’ guitars. The lacquer felt inches thick and it was a loud beast but it did lack sparkle – I can remember that much. My guitar is still going, played every day by the friend I sold it to in the mid 1980s. I’m always happy to see an EKO Ranger guitar and you can’t miss them: the scratch plate is completely unique.

Paul bought this EKO Ranger 12 string new in 1988. For 26 years that neck and body have been trying to resist the enormous load of double the usual amount of strings. It’s no surprise that something that old, carrying that much weight has structural problems and this guitar clearly has them. It’s like a bent old lady.

The first thing that struck me was the bridge. The forces pulling on it over the years have deformed the soundboard (the front of the guitar) substantially, pulling the back of the bridge upwards and the front of the bridge downwards. This creates a bulge behind the bridge and a depression in front of it by the sound hole.

As a result of this effective rotation of the bridge around it’s front edge, the 12 strings have risen up resulting in an action of about 3/4″ at the end of the fretboard and the bridge saddle has moved close to the nut resulting in messed up intonation. On closer inspection I could see that the bridge saddle was also bent forward (towards the nut) adding to the intonation issues.

Holding the guitar up and peering down the neck revealed (to my fairly novice eye) quite a lot of relief, almost certainly too much. There is a truss rod I could adjust but who knows what would happen after 26 years of disuse?

The headstock has some issues which I cannot be certain about yet. The lacquer has split on the back of the neck just below the headstock and I’m not sure whether the wood is splitting or just the lacquer. Short of an X-ray, I may not be able to reach a conclusion about this or affect any repair.

On the front side of the headstock the logo has a split all the way across it. I’m pretty sure that this is purely cosmetic as I can’t see any reason the whole headstock would be split.

So what can I do? What should I do? I’m not a fully-kitted-out or experienced luthier. I’m a newcomer to fettling guitars but, armed with the internet, a hunger to learn more, some tools and some patience I’ve promised to do what I can.

I talked to Paul about his relationship with this guitar because it mattered to me to find out how much it mattered to him and why. He’s had it from new, so it has sentimental value. But he brought it in so it’s not so important that he won’t risk letting me improve it somewhat. It has no commercial value so I can’t be spending a lot on trying to correct these problems – and that’s probably the #1 limit on what I will and won’t do.

Option 1

The cheapest and simplest way I could make the guitar a bit more playable for Paul would be to do the following:

• Wind down the adjustable saddle to its lowest position

• Replace the plastic saddle and file down the replacement to the lowest possible level

• Adjust the truss rod

• Replace the strings

• Polish the frets

This could reduce the action by 75% or more and improve the intonation considerably (although it still wouldn’t be perfect) while leaving the tilted bridge and distorted soundboard as-is.

Option 2

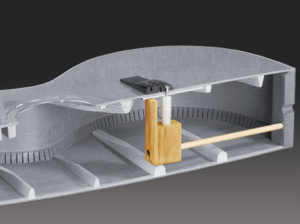

This would involve using a ‘bridge doctor’ – a product sold by StewMac in the US designed to support the bridge, stop its rotation downwards towards the sound hole and apply pressure in the opposite direction. This costs somewhere between $22 – $50 depending on the fixture you need. This may need to be done slowly and with the guitar in a humidified condition to make it a bit more flexible. If it were possible to straighten the bridge up somewhat, then the next step would be to replace the damaged saddle, lower it appropriately and adjust the relief in the neck.

Option 3

There seem to be some even more drastic treatments involving removing the bridge, applying heat and clamps to straighten out the sound board…I don’t know any more detail about what this would involve yet but I do know that it would require some expensive tools that it would make sense to have if you were a professional luthier but not me.